Davy Buck, the sexton at Lexington Presbyterian Church even before it was located in the center of town — and one of three African Americans buried in the otherwise all-white pre-Civil War Presbyterian Cemetery — is the subject of a new “Rockbridge Epilogue” by Neely Young, a historian and author of two books on slavery and its aftermath in the Rockbridge area.

The exploration of Buck’s life, which can be documented only in snippets, is the first of three parts on Young’s extensive “Epilogue” analysis of the institution of slavery in the 19th-century Presbyterian stronghold of Lexington and the tensions that arose in both the church and the governing regional Presbytery.

Buck was born in the early 1770s. (Records are sketchy.) He was enslaved by the family of Matthew Hanna, operator of a Lexington tannery, and Hanna’s descendants. Buck lived with the family on Henry Street until the 1840s.

He became the church sexton soon after the dedication of its first building in 1806, and stayed in that role until 1846. After passing a rigorous test that demanded solid knowledge of the Bible and of Presbyterianism, Buck was admitted to church membership in 1852. He died in 1855.

In an unusual arrangement for that day, Buck was an “independent contractor,” Young writes — paid directly by the church for his work. More customarily, the enslaving family would have received compensation for his labor.

The Lexington Presbyterian Church gave Young access to its 19th-century treasurer’s reports and other documents for his research. Even after Buck retired about age 70, the church took up a special collection for his benefit. His death was officially recorded, and it prompted an obituary in the Lexington Gazette, equally unusual then for a Black resident.

The second and third sections of Young’s “Epilogue” article examine the life of African Americans in the local religious community and the ties, sometimes genial but sometimes tense, among Lexington Presbyterian’s members on the wrenching issue of slavery.

Because of the author’s access to church records and the depth of his primary research, the article is one of the most important of the 58 “Epilogues” published since inception of the series in 2016, according to editors of the online journal.

Young is a 1966 Washington and Lee University graduate who earned his doctorate in American history from Emory University. His two Rockbridgethemed books are “Ripe for Emancipation,” tracing the Rockbridge antislavery movement from Revolution days, and “Trans-Atlantic Sojourners,” which follows two families, including that of Othello Richards of Rockbridge, as they led the repatriation of formerly enslaved Americans to Liberia.

The new “Epilogue” can be read, without charge, at www. HistoricRockbridge.org.

THE WHITE FRAME HOME on Henry Street of Mark Hanna is shown here before 1940, when it was demolished. Here Davy Buck lived for most of the time when he worked in Hanna’s tannery and as sexton of Lexington Presbyterian Church.

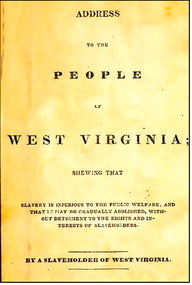

THIS PAMPHLET — published anonymously in 1847 but written by Henry Ruffner, a sometime pastor of Lexington Presbyterian Church — provoked much controversy, especially in eastern Virginia. It argued in favor of gradual emancipation, reflecting the view of most Lexington Presbyterians at the time.