Paintings Tell Stories Of His War Years

Revolutionary Moment

Eric Wilson RHS Executive Director

This article was written by Eric Wilson, executive director of the Rockbridge Historical Society, and co-chair of the regional committee for VA250: American Revolutions. Appearing periodically over the next three years, this series extends those anniversary reflections across four centuries of America’s revolutionary legacies.

When George Washington last appeared in this series of “Revolutionary Moments,” it was July 3, 1754: an ambitious 22-year-old colonial colonel in the Virginia Regiment, fighting for the British crown on the Pennsylvania frontier, at the tellingly named Fort Necessity. There, he surrendered to the French army, signing a document that, perhaps unwittingly, acknowledged his role in the assassination of a French officer. This did not seem a promising start, for the annals of history.

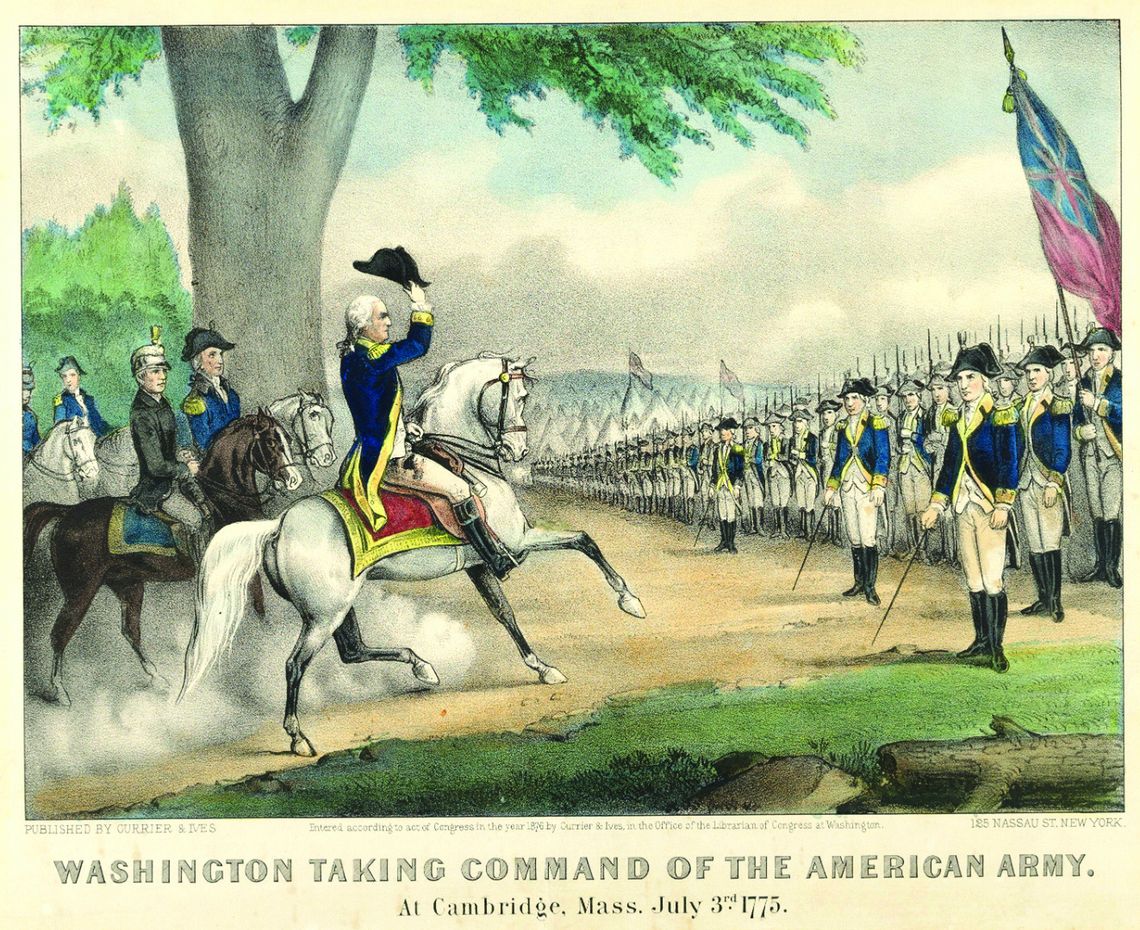

“History never repeats itself,” Mark Twain reportedly quipped, “but it often rhymes.” Sometimes uncannily, even dates and fortunes can echo, even distort. On that very same date, 21 years later, Washington would find himself 600 miles away, on the New England coast. For the first time there, the newly appointed general reviewed a raw American Army, established only three weeks earlier by the Continental Congress.

Breaking from Britain

In 1772, three years before that momentous turn of events, George’s wife Martha commissioned Charles Willson Peale to paint a grand three-quarter-length canvas of her husband: the earliest known portrait of the future American icon, and later donated to Washington and Lee University by descendants.

In hindsight, the choice seems curious: its assured, frontal pose featuring the now genteel, prosperous planter in the martial, royal red he’d donned during the French and Indian War. This, now a full 14 years after he’d resigned his commission as commander of Virginia’s colonial forces in 1758. Of course, neither Washington nor other revolutionary leaders yet knew that just four years ahead, a Declaration of Independence would signal a more definitive, collective break from the British empire, as colonial debates volleyed between compromise and armed revolt. Nor could they foresee the length and shifting odds of the eight-year global war that ensued, when Washington first encountered his new charges on the outskirts of Boston, on that hot summer day in 1775.

Most of those hastily-assembled 14,000 troops were drawn from a range of colonial militia across the region. And to temper the general’s expectations on arrival, Massachusetts’ Provincial Congress wrote to “your Excellency” that “the greatest= part of them have not before seen Service. And altho’ naturally brave and of good understanding, yet for want of Experience in military Life, have but little knowledge of [many] things most essential to the preservation of Health and even of Life.” More famously in the American memory bank, a number of those local soldiers had faced their first fire at Bunker Hill just two weeks earlier. Or only two months earlier, that April 19, now heralded as “Patriot’s Day,” when “the shot heard round the world” rang out on the Battle Green of Lexington, Mass.

ABOVE, this 1772 portrait of George Washington, uniformed as a British officer in the Virginia militia in the 1750s, is owned by W&L and currently on loan to the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation. AT RIGHT, John Trumbull’s 1780 portrait shows Washington near the end of the war, accompanied by his valet Billy Lee. (images from W&L Museums and the Metropolitan Museum of Art)

For the nation’s centennial celebrations of 1876, Currier and Ives published a widely reproduced print of Washington’s since-fabled arrival, now blazoned in blue. And rather than foregrounding him in singularity, they chose to flank him with long-running rows of his seemingly orderly, uniform forces.

Shock Troops, or Shocking Turns?

On that second, significant July 3 of Washington’s career, the freshly appointed commander-in-chief was credited with his characteristically steely reserve, while addressing these cobbledtogether and still-uneven “Yankee” forces.

En route, he’d written to Martha (whether confessing abiding doubts, or demurring with rhetorical convention), saying, “I have used every endeavour in my power to avoid it … But, as it has been a kind of destiny that has thrown me upon this Service ... it was utterly out of my power to refuse this appointment without exposing my Character to such censures as would have reflected dishonour upon myself, and given pain to my friends.”

In a run of other correspondence, however, the general was also quick to more candidly express his shock upon seeing what he now had to work with, and needed to work up. With this lot, he’d have to immediately face down the world’s largest and most powerful army. Already, more imperial ships were reinforcing Boston Harbor, arriving to anchor the defensive foothold of General Howe, settling in ahead of the Americans’ ultimately victorious 11-month siege.

But on August 20, six weeks after taking command, Washington wrote to the cousin who managed his Mount Vernon plantation through the war, using words that have been traditionally, discreetly excised from American textbooks. His ink dripping with exasperation, he confided: “Such a dirty, mercenary spirit pervades the whole, that I should not be at all surprised at any disaster that may happen. I daresay the men would fight very well (if properly officered), although they are an exceedingly dirty and nasty people.”

Hot war finally came to Virginia that Dec. 9, 1775, in the Chesapeake’s Battle of Great Bridge. The rebellious colony’s anxiously arming frontiers were soon enlisted, as men with ties to Augusta, Botetourt and soon-to-beformed Rockbridge counties found themselves summoned across the Blue Ridge, even traveling as far as the Battle of Brooklyn. On Aug. 27, 1776, Washington’s radically outnumbered, out-cannoned troops were overwhelmed there during their general’s first c rushing d efeat. F ortunately, a cannily-executed retreat (later called an “American Dunkirk”) allowed Continental forces to slip back across the East River at night, rally in Manhattan, and decamp to the Bronx.

After another defeat at Fort Washington on Nov. 16, they crossed the Hudson for another five long years of often-desperate campaigns, and surprise counter-attacks – before the British surrendered to American and French forces at Yorktown.

It would take over two more years for King George’s soldiers to fully withdraw from American shores, when General Washington led his troops into New York City on “Evacuation Day,” Nov, 25, 1783. At the Battery in lower Manhattan, the “boys in blue” found a flagpole that had been greased by redcoats to slow the removal of a last Union Jack. But in short order, they raised their new American standard. Congress’ Flag Act of June 14, 1777 – passed a year to the day after they’d established the Army – articulated its resonant symbolism: decreeing that “the Flag of the United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the Union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field representing a new constellation.”

Re-Presenting an American Hero

To close these counterpoints – a commanding officer now fighting against the enemy he’d formerly served; an army who had to learn how to lose effectively, and wait patiently to earn victory – let’s turn to a third portrait of Washington, still fighting in the midst of those campaigns.

In 1780, John Trumbull (an aide-de-camp to Washington who’d resigned due to a dispute with Congress) sidled to London, beginning his career as a professional painter on enemy shores, where he was later threatened with hanging. There, he studied with fellow American Benjamin West, the most celebrated artist of the era, a vital step in Trumbull’s own march to become the iconic painter of a young American Republic. Four decades later, in spite of their earlier impasse, Congress would commission Trumbull to paint four towering canvases, still hanging in the U.S. Capitol since the country’s 50th anniversary celebrations in 1826.

Among the nearly 250 skirmishes, battles, and sieges that historians reckon in the Revolutionary War, Washington commanded only nine in the field (winning but three, according to scholars at Mount Vernon today). But Trumbull – working afar from memory, and figuring him high above a fanciful naval battle on some Hudson- like River – executed what the Metropolitan Museum of Art accounts as “the first authoritative portrayal of Washington in Europe … and widely copied.”

Strikingly, the general isn’t backed by other soldiers here, but by his longtime valet, Billy Lee, whom he’d purchased in 1768. After following his owner throughout the war, Lee would be the only enslaved person immediately freed by Washington’s will 1799, which also granted him an annuity. Trumbull’s brush curiously exoticizes Lee, whose striking red turban gestures toward some of the imperial dimensions of a worldspanning war that would not formally end until the Treaty of Paris in September 1783. Surprisingly, two years after the victorious cries of Rockbridge and Virginian soldiers at Yorktown, the war’s very last battle, fought between the British and French navies, ended in the Bay of Bengal that June.

Together, these three colonial, revolutionary, and republican portraits variously figure Washington before his retirement as an American Cincinnatus: “returning to his plow” (or rather, to the world of his enslaved plantation), before a second rise to political prominence would see his election to the presidency in 1788.

Here in Lexington – chartered halfway into the war itself, and tellingly named for its revolutionary namesake – the conferred spoils of war, and grateful honors, would allow Washington to endow a young Presbyterian college on the Virginia frontier. Duly renamed Washington Academy, its colonnade would boast a toga-clad statue of “Old George” atop Washington Hall by 1844. Next door, William James Hubard’s 1856 bronze statue of Washington would similarly be erected on the grounds of the fledgling Virginia Military Institute. After its seizure by a Union army during its raid on Lexington in 1864, that statue would be ceremonially returned and rededicated two years later. Today, appropriately enough, it faces the Washington Arch on the eastern flank of Old Barracks.

Revolutionary Legacies In this first constellation of Revolutionary Moments, each installment has strategically featured George Washington, from diverse and sometimes surprising perspectives. While others ahead will move to different terrain, the opening quartet has set out to both ground and redirect attentions from the more familiar canon of stories we’ve come to tether to “The Founding Fathers.”

In the three years ahead, leading to the 250th anniversaries of the founding of Lexington and Rockbridge in January 1778, shorter retrospectives, and other guest authors, will fill out a broader canvas representing signal moments and goals in American history. That broader arc of “Revolutionary Moments” will illuminate other American dreams, and themes, that both extend and test these revolutionary legacies across four centuries, into our 21st.

Women’s stories will more visibly take the stage, using a wider lens than the 1976 bicentennial, with the archives and priorities then to hand: from Molly Pitcher manning the cannons at the Battle of Monmouth, to the 19th Amendment’s constitutional provision for Women’s Suffrage.

A century later, looking back from the American Civil War, our “War of Independence” may look more and more like an inaugurating civil war, itself. It tore apart resident loyalists, patriots, and indigenous nations, most of whom had to make their own hard decisions about who to side with, and how to negotiate and survive its wake.

The enduring Civil Rights freedom struggle – stretching from Reconstruction to contemporary legal cases and protests still today – attests to our nation’s continued push for individual liberties and civic ideals, and due witness to American resilience.

We hope you’ll follow the lead of Washington and those many others in these issues ahead, along with the rising tide of commemorative state and local programming that you can follow – and volunteer with – at VA250.org/ rockbridge.