Cadet Receives First Salute From WWII Veteran

The first salute is a quiet but profound military tradition. For new Army officers, it marks the moment their rank is recognized by an enlisted service member or veteran — often someone they deeply respect. In exchange, the new officer offers a silver dollar and a word of thanks.

On Thursday, that moment reached across generations and families.

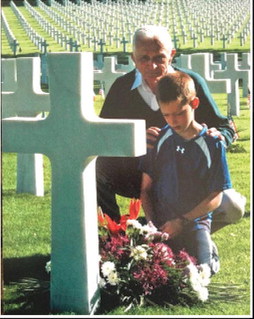

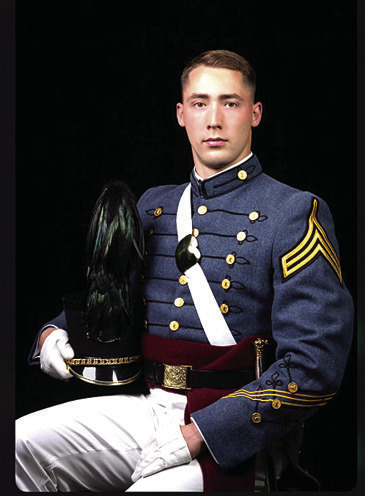

GRADUATING cadet Thomas Langston (seen in portrait at right) raised his hand for his first salute after commissioning last week to World War II veteran and family friend Jack Moran (in photo at top). As a youth in 2011, Langston had visited the grave of his great-great-uncle’s grave, Tommy Langston, with Moran in France (above photo).

When Thomas Langston raised his hand for his first salute after commissioning from Virginia Military Institute, it was returned by a man nearly 100 years old — World War II combat veteran John “Jack” Moran, who once served under Thomas’s great-great-uncle Tommy.

The extraordinary moment followed VMI’s commissioning ceremony (covered in greater detail on page B6). During the ceremony, the ROTC branches of VMI officially commissioned 170 cadets. Among the distinguished guests recognized was Staff Sgt. Moran, whose appearance drew a standing ovation from the crowd inside Cameron Hall.

After the main ceremony, the different military branches split up and went to different venues across the VMI post, for individual oaths, first salutes, and pinnings. In Marshall Hall, among loved ones and fellow officers, Langston and Moran performed their emotional salute and silver dollar exchange. - Jack Moran still remembers the exact day: Dec. 16, 1944.

“That was the beginning of the Battle of the Bulge,” he said. “We were attacking an objective in the Saar Valley of France. Tommy Langston (the great uncle of Thomas’s father Tom, who brought this story to The News-Gazette) was my squad leader.”

Moran, then a 19-year-old rifleman in the 87th Infantry Division’s 347th Regiment, K Company, said their unit launched its assault at 2:30 that afternoon, near the town of Obergailbach, France. Unbeknownst to them at the time, German forces had begun a massive counteroffensive —now known as the Battle of the Bulge — that same morning roughly 140 miles to the north in the Ardennes.

Within days, Moran’s unit would be pulled from the line and rushed north to reinforce the collapsing front.

“We had no coats. No blankets,” he recalled. “We rode in open-bed trucks in the dead of winter. When we dug in, the ground was frozen solid.”

The fighting was instantly chaotic. Tommy Langston, who had just shared a grin and a breakfast ration with Jack hours earlier, was hit and killed. As Jack ran past, he saw the hole torn in Tommy’s chest.

Later that day, Moran was crouched in a rock pile when a lieutenant came up and asked who was left. “I said, ‘I think I’ve got one man alive, and four are dead.’ He looked at me and said, ‘You’re the sergeant now.’ Just like that. Because Tommy was gone.”

Moran, who now lives in Los Angeles and had flown in for last week’s commissioning, speaks calmly about those days but doesn’t sugarcoat them.

“If you have good luck, you might survive. If you have bad luck you die. That’s the truth of it,” he said. - For years, the Langston family knew almost nothing about Tommy’s death — just the date and location. The circumstances were a mystery.

Until 2003. Tom Langston had long been curious about the great-uncle he was named after.

“I didn’t know anything about him. We knew where he was buried, but that was it,” he said.

That changed when he connected with a researcher named Barbara Strang, who was working through the National Archives. She directed him to a memoir written by a World War II veteran named John Moran.

“I copy-pasted it into a Word document and searched for ‘Langston.’ Sixteen hits,” Tom said. “It was surreal. This guy had been with my uncle. He mentioned going into England together, France, all these stories. And then he wrote about seeing my uncle die. It gave me chills.”

Tom reached out to Jack. They spoke on the phone, then met in person in Los Angeles. A connection sparked — not just as researcher and veteran, but as something closer to family.

Soon after, they traveled together with Thomas, then a young boy, to Europe, retracing Jack’s steps through wartime France, Germany, and Belgium. They stood together at Tommy Langston’s grave at the Lorraine American Cemetery near Saint-Avold.

Jack had been there three times now. Thomas’s participation in this legacy from an early age led to a special relationship with Jack — a bond that became even stronger last week.

“This isn’t just a gesture or a tribute,” Tom said. “Jack and Thomas have their own friendship now. Their own connection. That salute meant something deep.” -At 99, Jack Moran is sharp, funny, and direct. He still carries a message he wants to share.

“Young people today need to know what we went through,” he said. “How we suffered and died. I wrote all this down because I want them to remember.”

During the interview last week in Lexington, Jack brought out a binder of typed memoirs, recounting his time in the war with clarity and precision. He pointed to maps, memories, names. His voice softened as he spoke of Tommy, going on to name the several other close friends he lost in that perilous stretch of the war.

“This isn’t something you can explain easily,” Tom said. “It’s not just about military tradition. It’s about honoring someone who never got to come home. It’s about connection and continuity.”

A mid a season when news surrounding VMI has often leaned contentious, Tom expressed quiet hope that this story might offer something different. He voiced concern that recent headlines had painted a harsh picture of the Institute, and he didn’t want to contribute to that in any way. But what unfolded this week, he said, was a testament to the enduring power of VMI’s core values: honor, history, and human connection.

After the ceremony, Jack and the Langston family traveled together to Gates, North Carolina — the site of Tommy Langston’s birth — to mark what would’ve been his birthday, May 18.

After the dust settled from the busy week, Thomas, the newly graduated cadet, reflected on the significance of the event in his life. “I think having Jack there with me [was] like a living bridge between nearly a century of service and sacrifice,” he said.

“I feel like history and legacy are coming full circle, not just as I begin my career, but as I’ve received a blessing from the greatest warrior I’ve ever met. Ever since I decided to serve, I made a promise to myself to carry Jack’s example with me throughout my career and throughout the rest of my life, and I intend to uphold that commitment indefinitely.”

As Tom had said prior to the ceremony, “There’s a lot of closure in this.” And with this closure comes a living continuation of a massive legacy.

AFTER THE COMMISSIONING ceremony, Thomas Langston poses with his mother, Beth Langston, World War II veteran Jack Moran, and his father, Tom Langston.

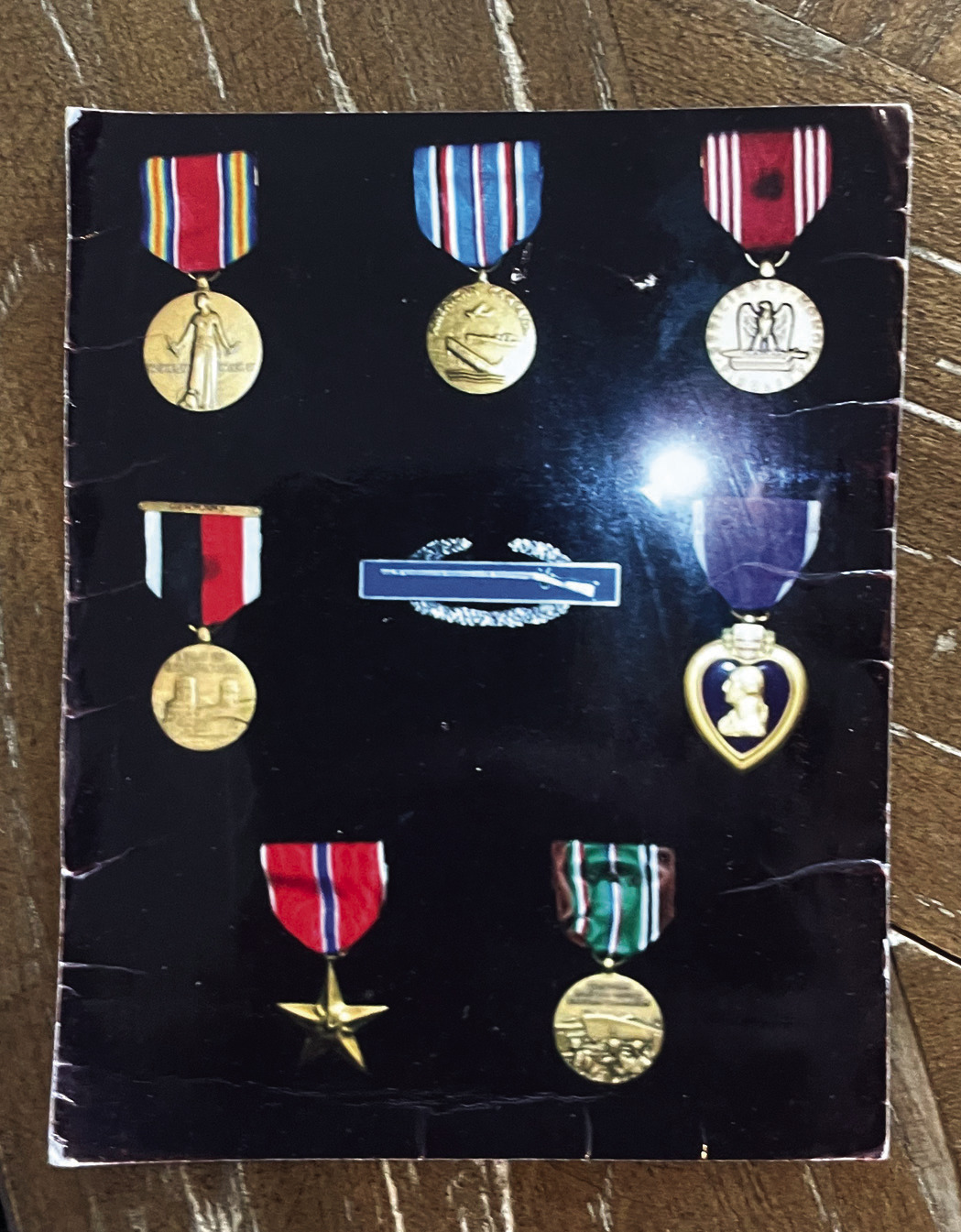

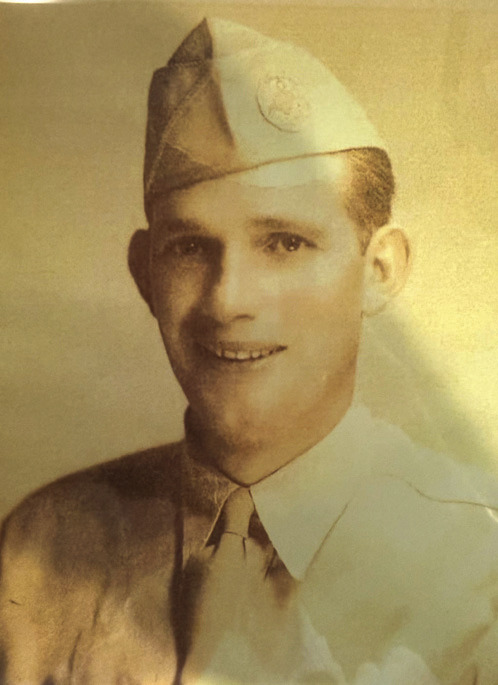

ABOVE is a young Tommy Langston, photographed before shipping out for service in World War II. He was killed in action in 1944. AT LEFT is an image from Jack Moran’s personal wartime archive, displaying medals and insignia from his time of service in World War II, including the Battle of the Bulge.