Editor’s note: This is the second of a two-part series about the Henry brothers of Rockbridge County. The author is Larry Spurgeon, president of the Rockbridge Historical Society.

The first part of this series told the background story of the four Henry brothers, free men of color who lived in Rockbridge County. It also detailed the life of Patrick Henry, the first caretaker of the Natural Bridge, through an arrangement with Thomas Jefferson, the owner. This part covers the lives of his brothers John V. Henry, Duncan Henry, and Williamson Henry.

John V. Henry (1798-c.1850)

John V. Henry, the youngest brother by a decade, registered as free in 1827, described by the court clerk as a “bright mulatto” and 5’6.”

In 1834, he lived with William Letcher, a contractor, and father of John Letcher, later Virginia’s wartime governor. That same year Henry was recommended by Samuel McDowell Reid, clerk of the court, to Henry Boswell Jones, a farmer near Brownsburg, to barbecue meat for 100 guests for the “Agricultural Society, & visitors at the fair.”

An N-G Series

By 1835, John V. Henry was employed by Washington College as “college servant.” His annual salary was $150 in 1841, increased to $300 in 1844.

Sally McDowell Miller, the daughter of Gov. James McDowell, wrote an article in 1883 about her Lexington memories, recalling a “splendid drummer” at VMI, Reuben Howard, a free man of color, who awakened the cadets and “put them to bed correspondingly early.” The Staunton Spectator observed that she had given Howard “ample justice,” but said “not a word about John Henry, the College janitor, and his tin horn! Many a cold winter’s morning, while Reuben beat the reveille at the Institute, ‘did Professor Henry’s’ musical blast arouse the writer to attend prayers in the College chapel.”

Henry purchased a house for $400 at an 1841 auction, located near Henry and Randolph streets. Four years later he emancipated his wife Sally and their children for “love and affection which I have and bear to me.” He had purchased Sally from Hetty Montgomery. Sally Henry filed a petition with the Virginia Assembly for “leave for herself and infant children Lavinia Mary & John to remain in this County as free persons of colour.” 24 justices met to consider the petition and three fourths approved it.

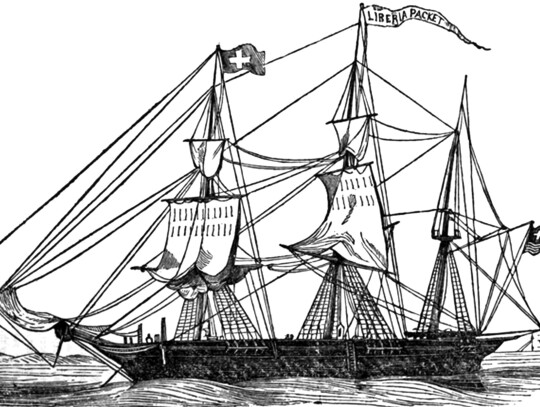

In early 1850, 24 Black people from Rockbridge County emigrated to Liberia on the ship Liberia Packet. The American Colonization Society (ACS) journal recorded the emigrants by family group; John V. Henry, 51, a teacher, his wife Sally, 40, and their children, Lavinia L, 18, Mary Julia, 17, and John P. W., 10, adopted son, William Henry, 4, and nephew Patrick Henry, 24.

One of the emigrants was Diego Evans, a barber who advertised that he sold cigars and ran a livery. He built a brick house that still stands on Randolph Street.

Samuel McDowell Reid wrote a letter of recommendation for Henry and Evans, stating they were “men of intelligence and piety, they have a deservedly high standing in our community and are actuated by high and patriotic motives.”

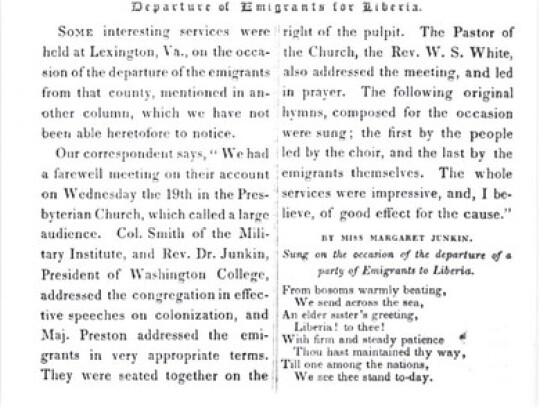

The ACS journal reported on the sendoff at Lexington Presbyterian Church on Jan. 19, 1850. Speakers included Col. Francis Henney Smith, superintendent of VMI, J.T.L. Preston, professor at VMI, and the Rev. George Junkin, president of Washington College. The Rev. William S. White led in prayer, and hymns composed for the occasion were sung by the choir. One of the hymns was written by Margaret Junkin, novelist and poet. The words were printed in full in the ACS journal.

The motives of the leading white citizens of Lexington to promote Liberian migration was in part benevolent, but to a greater extent a desire to reduce the population of free Blacks in the community.

Mary Julia Henry wrote to her friends in Lexington that her family rented a house in Monrovia on “Broad Street and Diego rented a house on the water side, which all the old settlers told him not, but he thought he could live there – being a good place to sell his goods. But all his family took the fever. We took the children home and they all got better, but Diego and his wife departed this life.”

John V. Henry formed a mercantile firm in Liberia with nephews Patrick Henry and Desserline T. Harris, who was secretary of state for Liberia. He wrote to Reid in June with a favorable report.

The following year, Rufus W. Bailey, an ACS agent, expressed frustration about his lack of success in getting more people to emigrate: “I should have realized all my hopes of a company in Lexington but for the deaths. Almost every prominent man in that company – Henry, Evans, McClure, Lee...” Like many emigrants to Liberia, John V. Henry and one of his daughters died not long after arrival.

Duncan Henry (c.1790-c.1834)

Duncan Henry filed a complaint in 1815 in the Staunton Chancery Court, alleging that after Martin Tapscott’s death he was hired out by the estate to two of Tapscott’s brothers, Henry and then John, where he remained until the death of Henry B. Tapscott. He then “removed” to Rockbridge County. The new executor of Tapscott’s estate, Thomas Rowand, half-brother to Henry B. Tapscott, attempted to deny Duncan’s title to freedom, and hired James Mc-Dowell of Lexington to seize him “forcibly, subjecting him to slavery.”

THIS American Colonization Society Repository Journal article reports on the 1850 sendoff at Lexington Presbyterian Church for the 24 Black people sailing to Liberia. John V. Henry was among those.

JOHN V. HENRY’S family and others from Lexington sailed on the Liberia Packet to Liberia in early 1850. The ship made many crossings for Liberian emigrants.

.jpg)