From Cave Mountain Mission School To Thunder BRidge Arts Center

Editor’s note: This is the first of a two-part series about the history of the former Civilian Conservation Corps property in Arnolds Valley. Part I begins with the first known use of the property, the Cave Mountain Mission School in the 1920s, offers a timeline of the property’s different uses, then covers the CCC. Part II, which will be published Feb. 25, looks at the property’s use as the Natural Bridge Juvenile Correctional Center and its use today as the Thunder BRidge Arts Center.

Beneath the shadows of Thunder Ridge, in the Jefferson National Forest, at the far end of Arnold’s Valley, sits a facility that once was a Civilian Conservation Corps camp (CCC), then became a federal reformatory, and at times was used as a forestry camp, all before it became the Natural Bridge Juvenile Correctional Center (NBJCC). It has currently morphed into a privately owned artisans’ and artists’ mecca.

The property is historically significant for three reasons: one, it was a CCC camp, and it is perhaps the best remaining example of one in the country; two, the state juvenile correctional center was in the forefront of prison reform, with its focus on training young men to return to society as productive citizens; and three, it was the first correctional facility in Virginia to racially integrate.

Cave Mountain Mission School

But long before these entities, another existed on the edge of the property. In the 1920s, a mission school was established. There were several of these around the county in its most rural outreaches. This particular one, known as the Cave Mountain Mission School founded by Miss Sally Bruce Dickinson, was written about by a Latin teacher from Lexington High School, Lucille Weaver, and it reads as follows: “Around 1920 the Presbyterian Mission Board appealed to Miss Sally Dickinson to organize a school in the remote, rough and almost inaccessible area called Arnold’s Valley or Cave Mountain in the southwestern part of Rockbridge County. Miss Sally had just spent approximately eight years in the Irish Creek neighborhood, diametrically opposed in location to Arnold’s Valley.

“Miss Dickinson, because of her success in working with people in other areas of the Blue Ridge Mountains, was persuaded by the Mission Board to come to Arnold’s Valley. She brought with her two young girls from the Farmville State Normal School, Miss Minnie Blanton and Miss Patty Garrett.

“In those days the journey to Cave Mountain was long and tedious, made on foot, on horseback, or in a farm cart or wagon. Miss Sally and her friends came by train to the Natural Bridge Station, then climbed aboard a straw-filled wagon which was to take them to their destination. The road was so bumpy that it was necessary to stop occasionally to retrieve a piece of fallen luggage.

“For a while the teachers lived with a Mr. and Mrs. Walter Johnson. Then two tents were acquired – one served as sleeping quarters, the other as a school. Before long a school building and a cottage for the teachers were ready for use – promoted undoubtedly by the community’s major industry, a large lumber mill.

“An essay written by Mrs. J. G. Austin states that Sally Bruce Dickinson had set up four mission stations before coming to Arnold’s Valley. She was selected for this post because “she was known and trusted by the mountain people; she knew better than anyone else how to handle the mountaineers’ shyness, suspicion and sensitivity.”

“The women did the best they could with what they had or could get … The teachers found it necessary to teach their students, old and young, many things other than the basic 3-R’s, which certainly were not neglected. Elements of first aid, good health habits, nutrition, dental care and the virtues of cleanliness and sanitation had to be stressed. Fortunately, school was in session the year round, so learning was continuous, and time for instruction was adequate.

“Church services were held on Sundays and prayer meetings on Wednesday nights, but religious training was offered every day of the week. The people of the community responded favorably to the high Christian principles exemplified by the “mission ladies.”

“The fact that Miss Sally and her helpers were aware of the need for more ‘fun and games,’ especially for the young people, should not be overlooked. Such activities as ‘pie suppers,’ ‘trips to the valley for ice cream’ and other jaunts were memorable occasions. There were also sports and competitive games – some educational in nature, but fun nevertheless.

“Mrs. Austin said Miss Dickinson stayed in Arnold’s Valley five or six years and then retired permanently to her home – Springfield – near Hampden-Sydney, in Prince Edward County.

“About 30 years later, when Minnie Blanton Button came back to visit, she found Mrs. Johnson living in a new house with electric lights and running water. ‘Yes, it sure is a different world,’ Mrs. Johnson is quoted as saying.

“Mrs. Austin’s essay closes with the question, ‘Is it any wonder that a tear trickled down Mrs. Johnson’s cheek as she sat in the auditorium at the Natural Bridge High School and proudly watched her grandson march down the aisle and receive the first high school diploma ever awarded to a child from the Cave Mountain Mission School?’

“Thus we have another chapter in the life of Sally Bruce Dickinson and another indication of the fruits of her unselfish love and devotion to people who needed her.”

Timeline

This property has been utilized fully over the years for an assortment of endeavors. Below is a timeline for the use of the property.

1920s - Cave Mountain Mission School 1930s - (early) Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp 1930s/late and early ‘40s - According to Joe Hawes, long-time teacher and administrator at the NBJCC, “After the CCC camp closed, the U.S. Army got interested in it and came in there and they trained mountain artillery. If you know what you are looking for and go back in those pine trees, you can find where they were shooting their howitzers. You can find pot holes. And those guys who were trained there used what they call pack-howitzers. A howitzer is more like a mortar, not a cannon. You can drop a shell into wher- ever you want.”

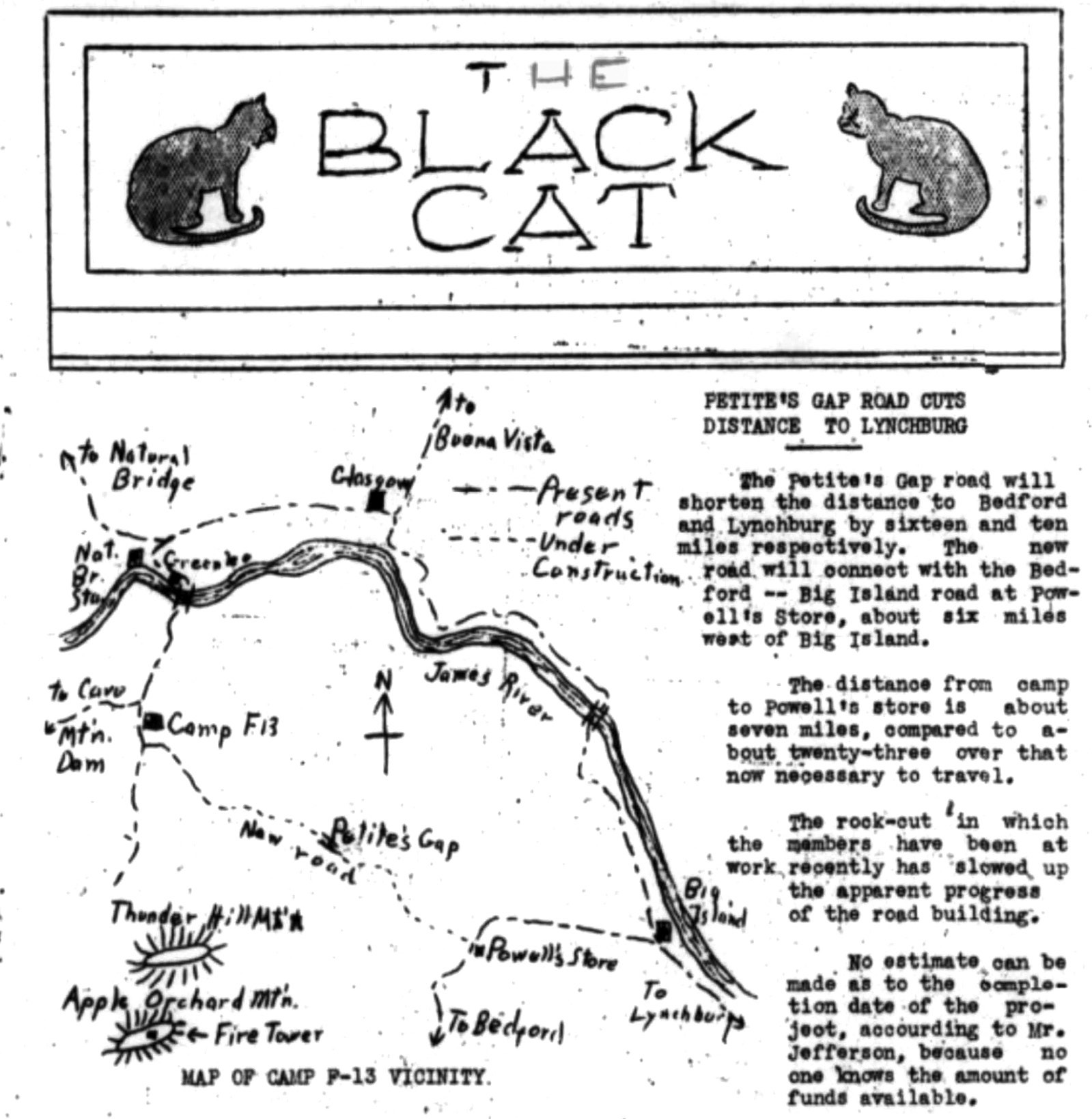

THE BLACK CAT was the name of a newsletter that kept the CCC workers informed about what was going on at the camp. The page from this issue includes a map showing the planned Petite’s Gap Road that would be built by CCC workers. The road shortened substantially the traveling distance from the camp to Bedford and Lynchburg.

1945 - The camp was transferred to the Federal Bureau of Prisons for use as a federal reformatory. The bureau operated the facility as an honor (low security) camp for delinquent boys until 1963. (This is the period when the infamous Charles Manson was there).

1964 - The commonwealth of Virginia leased the facility for juvenile reform. It became the Natural Bridge Juvenile Correctional Center (NBJCC). c1964 - Forestry camp. As stated by Hawes, “Since the learning center was leased to the state of Virginia, we had a forestry crew of about 15-18 boys that worked with the U. S. Forest Service. They cut trails. They killed undesirable trees. They had these things called hydro hatchets. You had a backpack that had brush killer in it and you had a special hatchet that you’d go around whacking the trees which injected the killer. The poison was 245T.”

1973 - Camp New Hope was opened on the property of NBJCC. This camping area was developed to provide a camping/ wilderness experience for youth from all of the juvenile correctional centers. Access to Camp New Hope was eventually expanded to youth under the supervision of the Department of Juvenile Justice’s Court Service Units, local residential programs, Boys and Girls Clubs, and other wilderness programs. According to Hawes, the idea behind Camp New Hope was to make it a division-wide camping program. Kids from other centers would stay a week or two and would use ropes and initiative courses to build confidence and team work.

1999 - Chapter 935 (The 1995 Appropriation Act) authorized the Department of Juvenile Justice to enter into an agreement with the federal government to purchase the NBJCC property. The department purchased the property in September 2000.

2009 - NBJCC was shuttered. 2021 - The property was purchased by James and Karen Pannabecker to operate an artist retreat in addition to campground facilities.

Civilian Conservation Corps

When Franklin Roosevelt was elected president in 1932, his innovative plan to heal the country during the Great Depression was called the “First New Deal.” The New Deal focused on the 3 R’s – not Reading, wRiting, and aRithmetic – but Relief for the unemployed and for the poor, Recovery of the economy back to normal levels, and Reform of the financial system to prevent a repeat of a depression. From the first R, came the Civilian Conservation Corps – the CCC.

The CCC was a voluntary government work relief program that ran from 1933 to 1942. It was created to supply jobs for unmarried and unemployed men 18-28 years of age. It was said that, “… an individual’s enrollment in the CCC led to improved physical condition, heightened morale, and increased employability.” Further, “The CCC led to a greater public awareness and appreciation of the outdoors and the nation’s natural resources, and the continued need for a carefully planned, comprehensive national program for the protection and development of natural resources.”

Roosevelt brought two “wasted” resources together – young men and land. The CCC workers, nationwide, planted more than 2.3 million trees, constructed 126,000 miles of roads and trails, built dams to create lakes for recreational purposes, and laid 100,000 miles of telephone lines through national forests. These are only some of their accomplishments. This part of the New Deal was really the very first effort of conservation of our national lands. Throughout the country millions upon millions have reaped pleasure in our national forests because of the accomplishments of the CCC.

In its heyday the CCC employed half-a-million men in more than 2,500 camps, with 2.5 million men enlisted during its nine-year existence. Each man earned $1 a day which was usually sent back to their families.

Eleanor Roosevelt organized a counterpart of the CCC called She-She-She Camps (formerly called the Federal Emergency Relief Association) for unemployed women. There were 90-some camps across the country which served about 8,500 women. She voiced that, “As a group, women have been neglected in comparison with others … And throughout this depression have had the hardest time of all.” These camps were integrated as the CCC was not. The allowance for women was the same as that for men in exchange for 56-70 hours work per month on camp projects. The tasks involved working in the forest nurseries, maintenance of the barracks, housekeeping and kitchen duties, along with instruction in economics and cooking. Historian Joyce L. Kornbluh wrote, “the She-She-She camps were seen as a social aberration. … The camps challenged the status quo by suggesting that women might go beyond their roles in the home to play extended, or different, roles in the workplace, in the labor force, and in public life.”

The impact of President Roosevelt and the First Lady was unprecedented in terms of women’s rights and conservation. The nation owes them many thanks for recognizing women as important in the social order and for the beauty begun and maintained in our National Forest and protected lands.

CCC Built Cave Mountain Dam

Research did not reveal that there were any She-She-She Camps in Virginia but there were more than 80 CCC camps in Virginia, one of which was located at the Natural Bridge property in the Jefferson National Forest in what was known as the Glenwood District.

Hawes related that the residents of this camp were veterans and a bit older than the normal attendees at other camps. The main two accomplishments of the men here were the building of the dam to create Cave Mountain Lake and the building of a forestry road called Petite’s Gap Road. According to a Roanoke Times article, “other incidental projects include the beautification of present roads on government land in this forestry district and timber stand improvement work, which consists of cutting, or fiddling so they will die, trees of undesirable species now growing in the forest. … They have also built 15 miles of new telephone lines and are now maintaining around 75 miles of line.”

Of particular interest was the development of the Cave Mountain dam and recreational area, which is about five miles from Natural Bridge Station and just up the road from the camp. The CCC workers built a dam 30 feet high and 100 feet long. This dam backs a body of water that covers six acres. According to The Roanoke Times, plans were then made for further development which would include the construction of a playground, diving platforms, camping and picnicking grounds, latrines, and numerous other improvements.

While the camp was in operation the residents created a newsletter published every six to seven weeks. The newsletters covered some of the actual work that was done but focused more on the social life there. The newsletter was called the Black Cat. It got its name because of some superstitions at the camp. Several involved the number 13; for example, there were 13 stones around the flag pole; the Camp was called Camp 13; it was established on July 13, 1933, and there were 13 trees around the officers’ quarters. That was enough “hoodoo” to come up with the name.

The paper claimed to disseminate the lowdown and dirt about everyone connected therewith. The many volumes of the Black Cat can be found at Virginiachronicle.com. The newsletters contained sketches, poetry, some history, work projects and social life entries. (An entry about the Cave Mountain Lake project follows as well as pictures of the dam construction from the 1930s.)

Also found in the Black Cat was an entry about the Petite’s Gap forestry road that the CCC workers built. It reads: “The Petite’s Gap road will shorten the distance to Bedford and Lynchburg by sixteen and ten miles, respectively. The new road will connect with the Bedford Big Island road at Powell’s Store, about six miles west of Big Island. The distance from camp to Powell’s store is about seven miles, compared to about 23 over that now necessary to travel.”

As far as the social life at the camp goes, there is plenty of information to be found in the newsletters. Surprisingly, there were many cultural, social and educational opportunities brought to the camp. The Black Cat tells of the first dance that was held at the camp where more than 100 guests from the neighboring towns were present. The Washington and Lee Orchestra provided the music and dancing went on until 1 a.m. On another occasion, “Your Uncle Dudley,” a Broadway hit, was performed at the camp.

There was no lack of entertainment for the young men. These men knew how to work hard and play hard and seemed to have made the most of the opportunity provided by Roosevelt.

According to Hawes, “The CCC died largely because of WWII. The military figured out the vets who were highly trained were the kind that you’d want to get your hands on for military service. This was true for other CCC camps too. Where else could you get guys that were physically fit, used to being outdoors, used to a military command structure – it was like they fell out of heaven.”

CCC WORKERS pose in formal attire for a photograph that was taken at the camp in the 1930s.

CONSTRUCTION of the Cave Mountain Lake dam was one of the major accomplishments of the CCC workers. The six-acre lake that was created became a recreation area with other amenities for area residents to enjoy.