RHS Explores Black WWII Soldiers And Workers In Rockbridge

Editor’s note: This article was written by Eric Wilson, executive director of the Rockbridge Historical Society and regional co-chair of the Virginia250: American Revolutions committee. Other local Black History programs will be featured in these pages later this month.

The Rockbridge Historical Society’s annual Black History Month series turns to World War II this year: honoring the range of local African American servicemen and women; broader national and global war efforts to win the Double V campaign against fascism abroad, and Jim Crow at home; and the continued push to integrate American women into wider military roles.

Upcoming Events

On Feb. 10 at 6 p.m. at the Rockbridge Regional Library in Lexington, a free screening of “The Six Triple Eight” will seed a “Revolutionary Films” discussion of women’s leadership in sorting the moralesapping gridlock of mail sent to soldiers fighting in Europe.

On Feb. 15 at 3 p.m. in the Lylburn Downing Middle School cafeteria, a slideshow presentation by RHS Executive Director Eric Wilson will highlight profiles of local Black World War II soldiers, contextualized by film clips about the (de)segregation of U.S. armed forces at large. To further crowdsource RHS’ archive of family memorabilia and oral histories, a roundtable of selected community panelists will round out the event, concluding with an open microphone inviting the audience to share family histories of service and sacrifice.

On Feb. 25 at 6 p.m. at the Rockbridge Regional Library in Lexington, the RHSVA250 series concludes with a “Revolutionary Books” discussion of Michael Delmont’s best-selling “Half American.” Written for a popular audience, his storyline chronicles Americans’ diverse commitments to combat global tyranny and American racism, while jointly winning “The War of Supply” on the front lines, and through homefront manufacturing. Copies of Delmont’s book can be readily found online, or loaned by local public and university libraries. Group discussion will also be interspersed with clips from Ken Burns’ 15hour series, “The War,” as well as other short excerpts from recent feature films and documentaries. See RHS Instagram and Facebook for more updates, digital video previews, and excerpts from the text.

A Poetic Prologue

The assertive, propulsive pair of words titling this article riff on the famous first and last lines of one of Langston Hughes’ most celebrated poems, one which I teach annually with local middle and high school students. “I, Too” was written in 1924 while Hughes was in Italy: still a generation before World War II, and shortly before his return to the United States to help fuel an emergent ‘Harlem Renaissance’ with his groundbreaking debut volume, “The Weary Blues.”

Its opening affirmation, “I, too, sing America,” deliberately echoes the precedent strains of “I Hear America Singing,” written by Walt Whitman, that other epic American bard from New York, and Hughes’ own noted model and influence. The poem’s final line, “I, too, am America,” evolves to an even more authentic, existential affirmation of selfhood. Through his labor and patience, the narrator’s confidence has grown beyond words and songs, figuring himself as the “darker brother,” once “sent to the kitchen,” who can now “laugh,/ And eat well,/And grow strong.”

During World War II, Hughes published his pioneering volume “Freedom’s Plow” (read for the troops and stateside listeners on NBC Radio on March 13, 1943) as well as the fearless lyric address, “Will V-Day be Me-Day, Too?” published in the “Chicago Defender” in 1944, voiced by a narrator who signs off as “G.I. Joe.”

Hughes’ insistent advocacy for “The Double V Campaign” had been shaped a decade earlier, while working as a war correspondent during the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s. O ften u nder fi re himself, he covered American troops who’d volunteered for the first chance to fight in integrated units in the “Abraham Lincoln Brigade.”

His wary eye compared the foreign tyrannies of Hitler, Mussolini, and Franco with the native racism of Jim Crow, a theme he’d return to in one of his longer poems, published for “Esquire” in 1936, fronting the insistent refrain, “Let America Be America Again.”

While Hughes’s words and aims have been torqued over time, its opening stanza poignantly, purposefully signals both national pride, and betrayal: “Let America be America again./Let it be the dream it used to be./Let it be the pioneer on the plain/ Seeking a home where he himself is free./(America never was America to me.)”

Global Contexts and “The Double V” Campaign Lyrical phrases provide one evocative register of wartime experience, whether under fire or in later reflection. Their public words add to the records of journals and family scrapbooks; the memorabilia and minute books from VFW and American Legion posts still operating here today; and the oral histories shared by families.

WINNER of seven NAACP Image Awards, Kerry Washington stars as Maj. Charity Adams, who led the 6888th Postal Directory Battalion, the first and only all-Black, all-female unit deployed overseas.

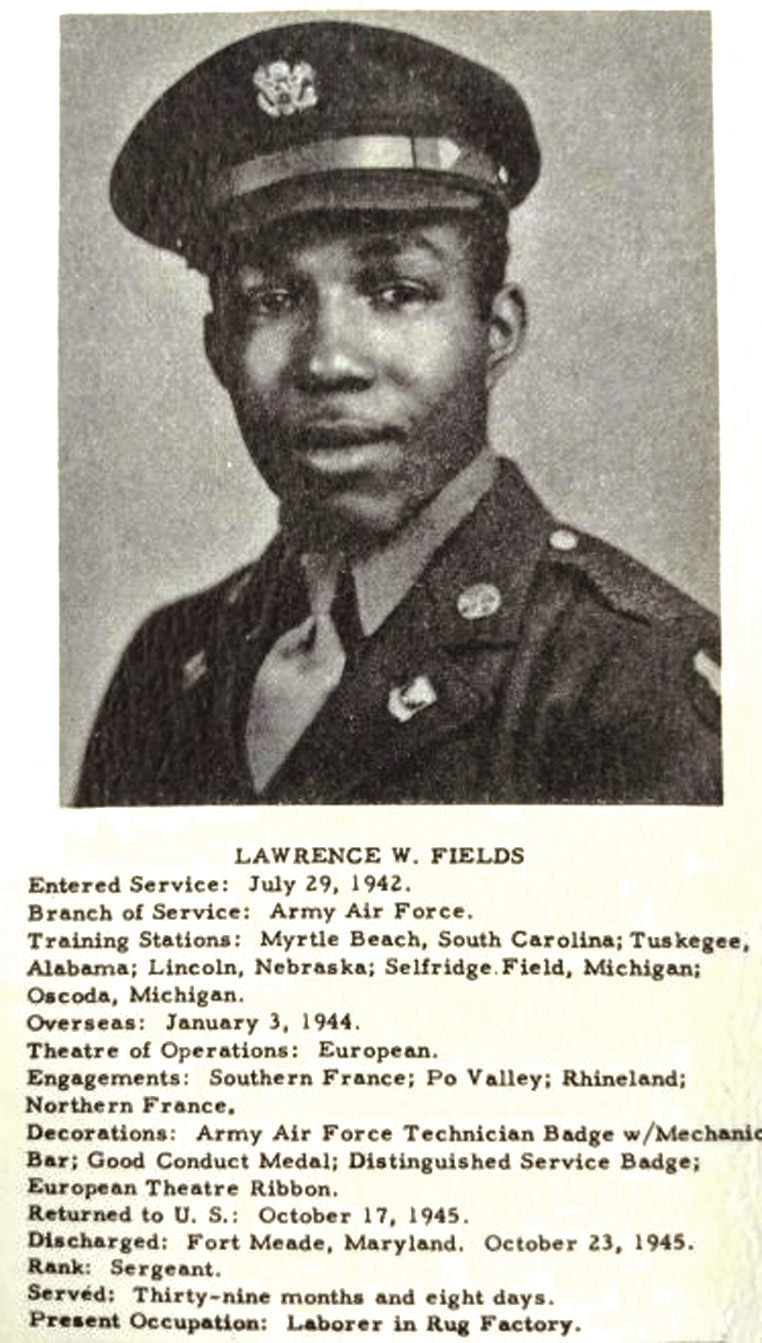

BUENA VISTA’S Sgt. Lawrence Fields trained as a mechanic, then joined the fabled Tuskegee Airmen. After his service, he returned to work in Glasgow’s “Rug Factory” (now Mohawk). Several of the 200-plus employees who served in the war will be profiled by RHS and descendants at the Feb. 15 program.

At the turn of 2026, just over 66,000 World War II veterans still survive, with an average of 234 dying daily. More intimate family testimonies – no less than veterans organizations and historical societies actively recording first-person witness – are now all the more critical.

More specifically, Black soldiers, families, churches, and community organizations would increasingly advance what came to be known as the “Double V” campaign, for the double victories to be fought for abroad and at home. The phrase was first articulated in a subscriber’s letter published in the Jan. 31, 1942, issue of the “Pittsburgh Courier,” then the nation’s most widely circulated Black newspaper.

Locally, the African-American broadsheet “The Lexington Star” survives only in a few pages from the 1920s. But regionally, readers could follow the campaign in Black newspapers such as the heralded “Richmond Planet” (est. 1882) and the Roanoke Tribune (est. 1939). With its masthead declaring it to be “The Only Negro newspaper published in South Western Virginia,” the Tribune’s stated purpose was: “1) to promote self-esteem; 2) to encourage RESPECT for self and differences in others, and 3) to help create lasting vehicles through which diverse peoples can unite on some common basis.”

In the book to be discussed on Feb. 25, “Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II Abroad and at Home,” Dartmouth history professor Matthew Delmont, an expert on the American Civil Rights Movement, notes: “Over one million Black men and women served in World War II. Without their crucial contributions to the war effort, the United States could not have won the war. And yet the stories of these Black veterans have long been ignored, cast aside in favor of the myth of the ‘Good War’ fought by the ‘Greatest Generation.’

“Their bravery and patriotism in the face of unfathomable racism is both inspiring and galvanizing. In a time when questions regarding race and democracy in America remain troublingly relevant and still unanswered, this [retelling of World War II] is both urgent and necessary.”

Among those more celebrated units are the “Black Panthers” (the 761th Tank Battalion featured in Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s 2004 book, “Brothers in Arms”), and the 92nd Infantry Division. Popularly known as the “Buffalo Soldiers” (formed by Congress in 1866 as the first all-African American peacetime regiment), the 92nd was the only all-Black U.S. infantry division allowed to serve in direct combat during World War II. Their accomplishments – and struggles against both their own white officers, and the racial prejudice and armored counterattacks of Nazi soldiers – are jointly featured in Spike Lee’s award-winning film, “Miracle at St. Anna,” with clips to be screened during the Feb. 15 slideshow.

Delmont also singles out the traditionally overlooked “Red Ball Express,” the massive truck convoy system urgently organized in August 1944 to sustain the breakout from D-Day. Future Civil Rights leader and martyr Medgar Evers was a soldier and driver in the unit.

Other pioneers included 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion, composed of 855 Women’s Army Corps soldiers, the only all-Black, allfemale unit deployed overseas in World War II. In 2022, surviving veterans were belatedly honored with the Congressional Gold Medal, recognizing their critical accomplishments in sorting out the deadlocked Allied mail crisis. Their ingenuity and resilience are featured in Tyler Perry’s 2024 film, “The Six Triple Eight” (rated PG-13, winner of five NAACP Image Awards). Middle and high school students are especially invited to the RHS screening at the Lexington library on Feb. 10, with a free pizza party to fuel conversation.

Local Profiles

My own presentation at Lylburn Downing will highlight several local portraits of combat veterans and logistical service, complemented by local descendants’ own witness.

As just one example, Tuskegee Airman Sgt. Lawrence Fields, pictured with this article in dress uniform, was decorated for his service as an aviation officer in the Army Air Force. Like many others in Buena Vista and Rockbridge, he, too, returned to work in the local “Rug Factory” (now Mohawk Industries). On Feb. 10, 1943, federal and state dignitaries had traveled there to present the “Army-Navy Award for Excellence in Wartime Production to the Men and Women of the Blue Ridge Company, Glasgow, Virginia.” First established as James Lees & Sons Carpet Factory (only five years before the war, in 1934), the factory proved a crucial agent in weaving the extraordinary supply of canvas required for uniforms, tents, and the millions of bags needed for transportation and other warfront needs.

Fields’ portrait appears in the comprehensive 1948 Buena Vista World War II Service Register, published by its American Legion Post No. 126, alphabetically searchable, though racially segregated. (The register is now freely available on the RHS website.)

Fields is one of only seven Black servicemen to be featured with a contributed photograph and full service details, among the 46 “Colored Men” whose names are listed at the back of the register. O verall, 734 fallen and living veterans – male and female, white and Black – comprise the city’s commemorative tribute, the only one of its kind in our area. A photo of the three men who led the local draft board concludes the communal litany, headed with the epilogue: “ALL IS FORGIVEN.”

Inviting Family Witness With the support of W&L’s DeLaney Center, local university and high school students, and RHS and VA250 volunteers, research continues into the wider sweep of local men and women who served in World War II (as also with our continuing oral history project centered around the Vietnam War): across all branches, across the color line, during the rage of war, or the readiness of “peacetime.”

As we continue our nearcentury- long commitments to preserve and promote the histories of everyday life in the Rockbridge area, RHS invites community members to contact [email protected] or (540) 260-5091 to share their own family histories, photographs, and scrapbooks. W hile we hope many will feel called to share their tributes at the Feb. 15 program, we’re also prepared to audio or video record that witness more privately, or at greater length, at the RHS Museum.